My name is Majouna. I was born in Smara, Western Sahara but had to flee for the safety of my family. Upon hearing the news of the Moroccan invasion, my husband told me to take our children and meet him in Mhriz. I bought a donkey and a cart to carry a small tent and some food. I moved outside Eloun City and stayed there for two days. I would cook for my children in daylight; because we could not start the fire at night for fear that Moroccan military jets or their patrols would spot our location.

My husband was fighting with the Saharawi Liberation Movement, but he would come to check on us. After spending four days hiding, Saharawi fighters escorted us to Bir Tigasit where we met many other Saharawi civilians who were fleeing Western Sahara. We heard about the Tifariti bombing, and we decided to move to our final destination, the refugee camps. On our way there we got lost, but eventually we made it safely.

At the beginning of the refugee camps, life was very difficult. Women started to make mud-bricks to build the basic infrastructures, and some of them took military training in case they were needed in the battlefields. I trained for three years. I remember joking with one of our leaders: I told him it was time for me to retire after those three years.

My husband survived the war, but he died some years later. I have two brothers and a sister in the occupied territory, who I have seen only one time in 40 years, when we met in Mauritania. Living without them is one of the many sacrifices that I have to pay for refusing to live under the Moroccan occupation. I am old now, and I have just one last wish: to see Western Sahara become independent in my lifetime. This alone would be enough for me to wash away all the hardships and difficult times I have been through.

My name is Bashir Ali and I am a Saharawi poet. I started writing poetry when I was fourteen and I learned a lot from great Saharawi poets like; Dkhil Sidbaba, Mohamed Hadara, and Abadallahi wald Ahuidid. In the beginning I was influenced by their poems; I copied their style and my first poems were similar to what was trending at the time. I began by writing about topics such as nostalgic experiences, the beauty of women and natural landscapes, but my real start as poet was with the start of the revolution. My inspiration came from my reactions to things that I either witnessed or experienced, such as the occupation of Western Sahara. I saw a lot of large countries plotting against a small nation without reason, which was something that outraged me. It made me write of the determination, resilience, and strength of Saharawi people, as well as their unyielding desire to stand up for their rights.

The most personally meaningful poems I wrote were on national unity; these poems are closest to my heart.

Here is an example from my poem called Activists:

May I be far from selling out my people, my mother tongue, my homeland, my soul and the whole that I am part of.

What could be enough to replace these things?

No matter the bounty much I am given,

It will always be less than my nation and my friends.

In regards to the future of poetry, poetry will not die. As long as there is culture, there is poetry. Poetry and culture are intrinsically linked together. As long as the Saharawi have the traditions of making tea, wearing the Draa, wearing the Melhfa, eating camel meat, and living in tents, there is a guarantee that poetry will not die. As long as there is a taste for poetry, there will be a Saharawi poet to write it. If I were to advise young and aspiring Saharawi poets, I would tell them to be honest, modest, only recite upon requests, and never use poetry to spread hatred or indignation.

I was born in the refugee camps and raised in the Sahara Desert, where it’s extremely hot in summer, cold in winter, and the wind is able to blow over our tents. During the exile, we experienced what it means to be in need. This suffering we took lightly, or even accepted as normal, but it is not.

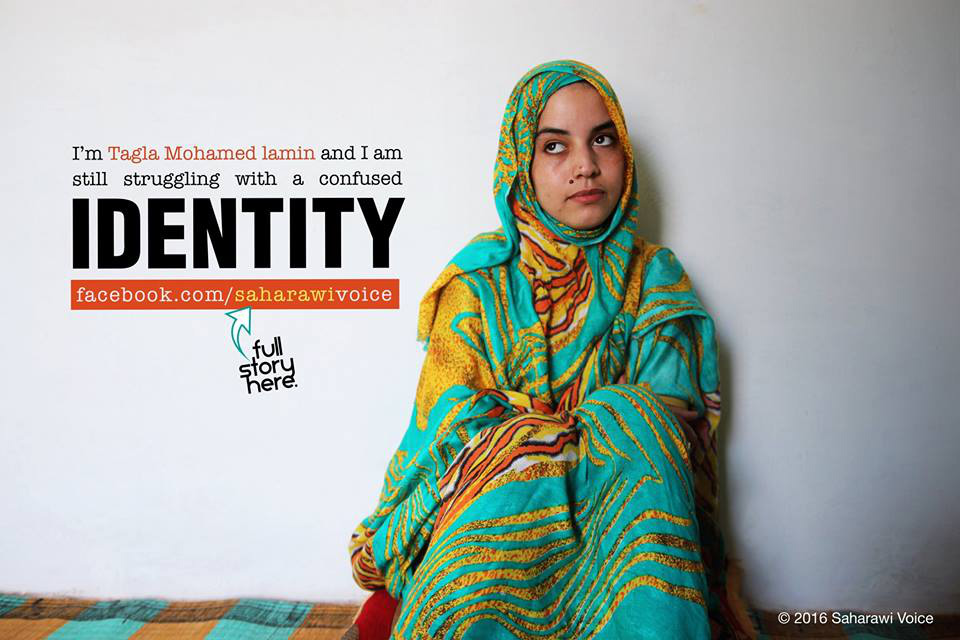

Saharawi children go to Europe to spend their summers. As a child, it’s a shocking discovery that not everyone in the world lives in refugee camps. Before visiting Europe, I had always thought it was normal to live in a tent and a sand brick home. But it turned out that the primitive life we live is something from the distant past of other nations. This discovery makes every Saharawi child ask haunting questions. Who are we? Where did we come from? What did we do to deserve this? Adults have always told us that we have to live in refugee camps because we were robbed of our country, but that answer was never enough for me to understand the injustice we lived through as children. It was during those summer vacations that we experienced a normal life. As refugees we considered that a very luxurious life, but for most of people in the world, it is normal.

The most difficult challenge we faced as we grew up was the time we spent studying outside the camps. Saharawi students have to leave their homes and go to one of following countries to study: Algeria, Libya, Spain, or Cuba. In my case, I went to Algeria for middle school, high school, and university. We had to adapt to a new society, a new culture and last, but not least, a new dialect. We studied Algerian history instead of Saharawi history. Every day, we sang the Algerian anthem instead of the Saharawi anthem. It took me nine years to finish my studies, and the price was high.

At first, I thought it might not seem like such a bad thing to live and learn in another nation, even though we were immersed in another nation’s history and culture at such an impressionable age. But imagine how that happens at the expense of our own culture and history – the result is a confused identity, an identity crisis, and this is what most Saharawi students have to go through. Some of them succeed in balancing and adapting to the new culture, yet preserving their own, but I think that most of us still struggle with it.

My name is Khalihena Saadbuh. I’m 22 years old and, unlike most Saharawi’s I am an only child. My father owns a small store that carries kitchen and household supplies, and sometimes I help run the store in the evenings or on the weekends, but my day job is working as an English teacher in a local middle school.

I graduated from Essalam English School in May of 2014. I was very motivated to learn English because it’s the language of the world and it will be very useful in my future. I really enjoy writing too, about anything, really, but mostly about things that relate to the struggle my people have endured and our hope to be independent one day.

I enjoy working with my students. I feel satisfied with my work, as I believe I am helping the youth by giving them something that will enhance their futures. It’s not easy. Many students do not show the desire or motivation necessary to learn a second language, but others do.

It’s too difficult to write about your experiences that you have had in exile because the realities we face somewhat obligate you to ignore some aspect of life…to shut it out or become hardened by it.

We have passed through indescribable experiences here in the refugee camps, but in spite of what we have suffered from we have learned a lot–more than what you could ever learn in school. We have learned how we can be patient in despite being oppressed and displaced from our homeland. We’ve learned how to keep standing in the face of great challenges.

The future is always full of hope, but it’s true that it’s hard to talk about my hopes and dreams for the future because there is first the need for freedom. Freedom is the necessary foundation for anything else to be built upon. And so our people, for now hope only in that our right to our self-determination and to live once again in our unoccupied land.

Message to the world: We all must continue to educate ourselves and grow in the ability to change our situations for the better.

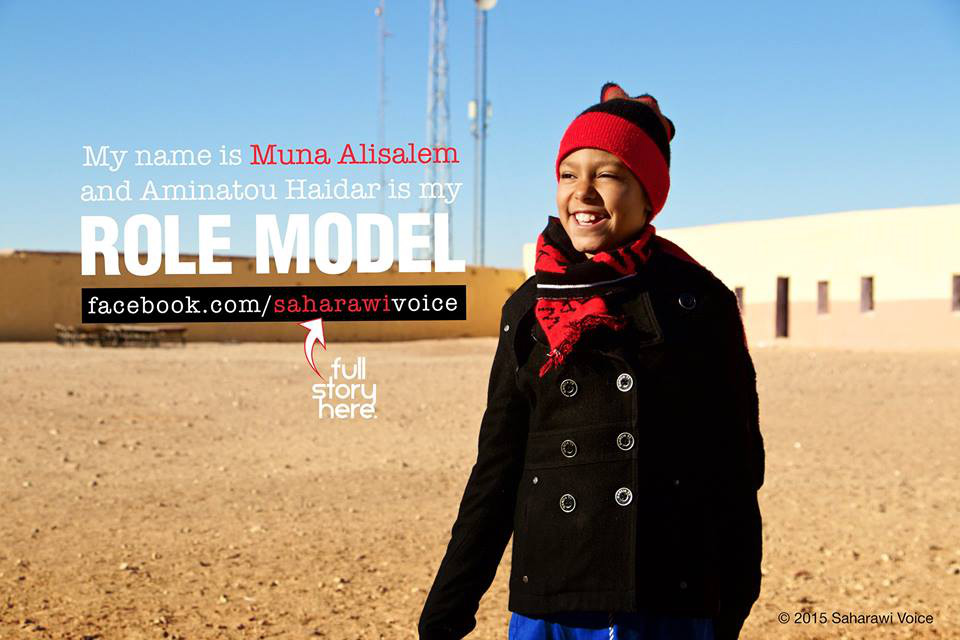

My name is Muna Alisalem, I’m 11 years old. When I grow up I want to be a teacher. In summer there is a program for Saharawi kids called “Summer in Peace.” As part of that program I had the chance to go to France. I liked the weather there because in the Saharawi refugee camps it so hot during summer. I felt jealous of the French kids because they have a country and they don’t have to suffer from the unbearable heat of summer like we do.

My role model is Saharawi human rights activist Aminatou Haider because she struggles for her peoples’ rights and freedom.

My message to the world is this; we are deprived from our country and we need your help to gain our freedom.